Since soon after I first taught my daughter Colleen to read back in the mid 1990’s, an experience that set me on this obsessive literacy journey, I have been ultra-aware of the crucial role segmenting plays in reading as well as spelling. Colleen was in 2nd grade and could memorize words like a pro– both in her basal reading stories and for her spelling tests. She looked the part but couldn’t read books she hadn’t memorized or spell the same words in her writing that she’d gotten correct on the spelling tests. She also couldn’t comprehend anything new she tried to read. As a result, my gentle little girl threw unfamiliar books across the room and wrote long stories that no one could decipher.

SEGMENTING WITH LETTERS

When I taught Colleen to read with Phono-Graphix back in 1997, I realized that teaching her to say the sounds as she wrote the letter(s) was a significant component that contributed to her reading skyrocketing in just 3 hours of instruction. She went from refusing to read ANY book she hadn’t had a chance to memorize to reading Bailey’s School Kids chapter books, typically an entire book in one sitting! At the time I didn’t know it was unusual for a struggling reader to become proficient at reading in just 3 hours. She’d been put in the gifted and talented program at school because of her high math scores and had never had remedial reading instruction. She hadn’t fallen apart enough by 2nd grade to warrant intervention and had fooled her teachers by being an expert pretend reader and rote memorizer of spelling words.

Even while teaching her way back then, I instinctually knew there was something to the instruction, especially insisting that she say the sounds as she wrote the letter(s), but I didn’t get why at first. After Colleen’s crazy and quick progress in reading, I began volunteering to teach quite a few friends’ children in the den at home. One of these students was a 10th grader from a nearby school district. His dad was a farmer and this young man could take apart and put together a tractor like a pro. He was the class clown in school; his mom said he used that skill to avoid anything to do with reading books and spelling. He hated reading and writing.

There are certain pivotal events in one’s life, and this young man was pivotal in my growth in teaching reading because at the time, I had no clue what to think of how he presented. When he came in I did a few assessments, including having him read out loud before we started instruction. By doing this, I could observe if he guessed and skipped words, was choppy with his fluency, or mixed up the sounds in words. Much to my surprise, he read 1 ½ pages from the book The Best Christmas Pageant Ever accurately, fluently, and with expression. He had no idea…at all…what he’d just read and could not even tell me the general idea of what it was about.

As I began working with this young man, it was immediately apparent that he could not segment at all. He could memorize whole words well, and he tested only a bit below grade level on Word Identification (lists of real words) but many years below grade level in Word Attack (lists of pseudo words). I knew from that profile that he was a whole word memorizer. However, I was not prepared for how difficult segmenting and ‘saying the sounds as he wrote’ would be. I worked intensely with him on segmenting by looking at my fingers and not the word and each repetition he improved significantly. If the word was written and I asked him for the sounds, he would give me the letter name instead. By the end of the hour he was segmenting quite proficiently, even with the letters present, and we had done quite a bit of word work with sorts as well as multi-syllable words.

Before he left, I had him read the next 1 ½ pages of the same book. Again, he read accurately, fluently, and with expression. The tremendous difference is that he could tell me, almost verbatim, what he’d just read!

My sister-in-law, who worked in a school, was observing this session. After this student left she asked me what on earth had happened to make such a significant difference so quickly with this child. Back then, I had no clue. The mom reported back that the ‘miracle hour’ of instruction totally turned around his attitude toward reading and writing as well as his ability to do so.

Now, 24 years later, I have no doubt what happened because I’ve had the same or very similar experience with thousands of students at our center, as well as teaching classrooms in schools. What was it? Segmenting! Not just segmenting sounds orally, but segmenting and matching the sounds said with the spellings that represent them.

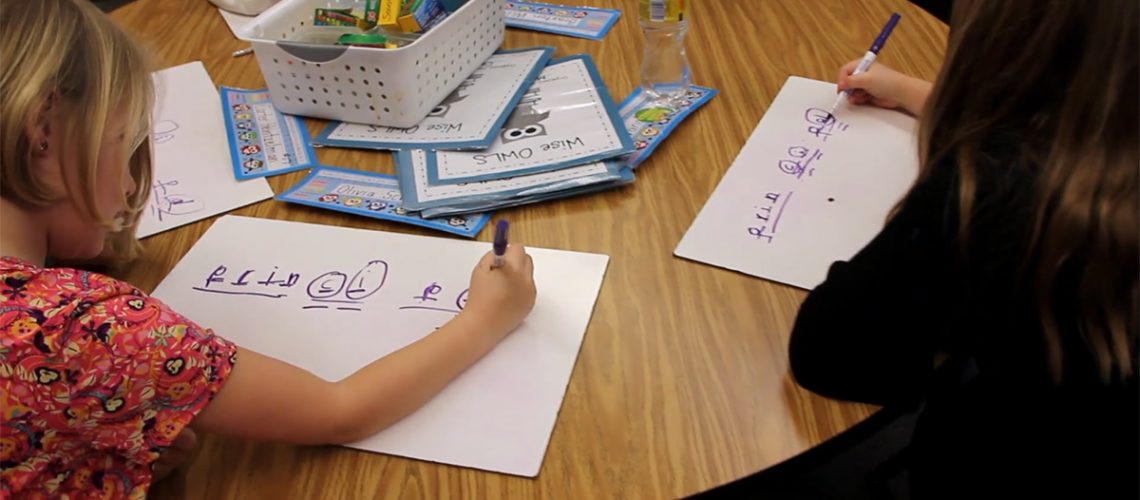

Gains with EBLI instruction are atypical whether the assessment is ACT or SAT scores, state assessments, DIBELS, F & P, Woodcock Johnson standardized test, or any assessment of reading ability. There are many components of EBLI instruction that lead to these gains, of course, but one of the main ones is segmenting sounds while matching the letter(s) or spelling to those sounds. It results in what seems to be miraculous student gains whether teaching Kindergarteners, middle schoolers, or adults. The results are not only monumental, the speed in which they happen is also turbo charged. How can less than 2 hours of instruction (total) result in 2-4 point gains on an ACT composite score…consistently and with thousands of students taught in a 1:1, small group, or whole class setting? Segmenting…with matching the spellings, is the key ingredient.

You can never have too much segmenting (again, not oral segmenting – students have to match the spellings with each isolated sound). I reiterate this to teachers we train and parents of students at our center repeatedly. Continuous blending when teaching students to read words or when reading in text is important transitionally with emerging readers as well as older students who are sub-literate. This strategy is necessary until they can blend well. However, we don’t want to make the mistake of assuming this means to get past the segmenting quickly or no longer pay attention to it. To learn more about the application of this process, check out our More of This and Less of That for Phonemic Awareness and Phonics webinar.

The correlation/causation of segmenting with comprehension and fluency has been glaringly apparent with students taught by EBLI trained teachers as the gains these students make are swift and significant. Why is that so? I have no idea. Where is the research? There is an abundance of research on the importance of segmenting and blending in early reading instruction. While we have copious amounts of action research by teachers and our team on the connection between segmenting with letters and the impact on fluency and comprehension, I haven’t found any peer reviewed research on this. However, just because there isn’t research on something does not mean it isn’t impactful; it just means it has not been researched yet. Fifty years ago there was no research about the importance of phonemic awareness on reading acquisition. However, Pat Lindamood, a Speech Language Pathologist, and many other practitioners had discovered this connection in the early 1970’s when teaching students. After seeing the amazing student gains, they then did research. My experience, as well as the experience of thousands of EBLI trained teachers, has revealed the connection between segmenting while matching phonemes/sounds to graphemes/letters and dramatically improved fluency and comprehension is very strong. I am hopeful that a wise researcher, or many wise researchers, will study this in the near future! If you are interested, please contact me as I’d be thrilled to be involved in and/or give input for such a research study.

Thousands of teachers who teach EBLI, the team at our center who coach teachers and teach remediation learners of all ages at our center, and I have experienced the rather unbelievable magic of segmenting sounds as you write spellings, in all words. Learners are taught how to do this crisply, not ‘mushy or slow blending’ or ‘continuous blending’, when writing spellings. Then they do it repeatedly until it becomes automatic. Along with improving fluency and comprehension at lightening speed, this strategy teaches the learners countless phoneme-grapheme (what sound goes with each spelling) correspondences as well as the patterns for placement in words.

With EBLI, saying each sound as you write and spell (and when reading challenging multi-syllable words during instruction for older students) is non-negotiable. It is, as one teacher said, ‘the magic fairy dust’. To accelerate student instruction and student gains beyond what we previously thought was possible, this strategy is a must!